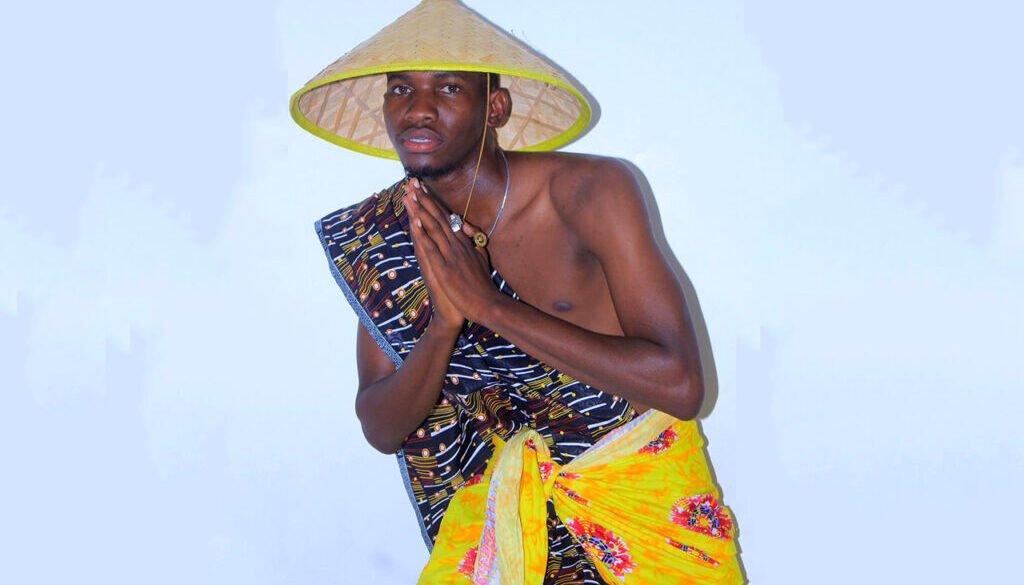

Thuto Retiyo Wayei culture story

Today’s era is where global sounds dominate, and a quiet revolution is stirring within the Wayei community. While many contemporary artists lean into English lyrics, often for broader appeal or perhaps a perceived sense of modernity, there’s a profound beauty and power in returning to one’s roots.

The Wayei people are discovering, or perhaps rediscovering, that their native language isn’t just a medium for communication; it’s a vibrant tapestry woven with history, identity, and an unparalleled artistic spirit.

But, in the heart of the Okavango Delta, where the emerald waters weave a tapestry of life, Thuto Retiyo, was born and raised amidst the Wayei tribe in the serene village of Seronga.

To emerge from the bosom of the Wayei is to carry a torch of dignity and a banner of pride, for theirs is a culture to brag about, a heritage to call their own. They are the children of the Delta, their lives intertwined with the rhythm of the seasons, their hands skilled in the ancient arts of ploughing, fishing, and hunting.

Through the veins of their land, they glide in Mokoro canoes, handcrafted from wood, truly at home on the water as a fish in the sea. The melodies of Retiyo’s native Wayei language are not just songs; they are whispers of preservation, a bulwark against the tide of silence that threatens to swallow his tongue whole.

“It grieves my heart to see the younger generation, adrift in a sea of other languages, their Wayei fading like a distant memory. When I ask why, the answer often strikes a chord of sadness: their parents, in a misguided attempt to ease their path, never spoke the language at home,” Retiyo said in an exclusive interview.

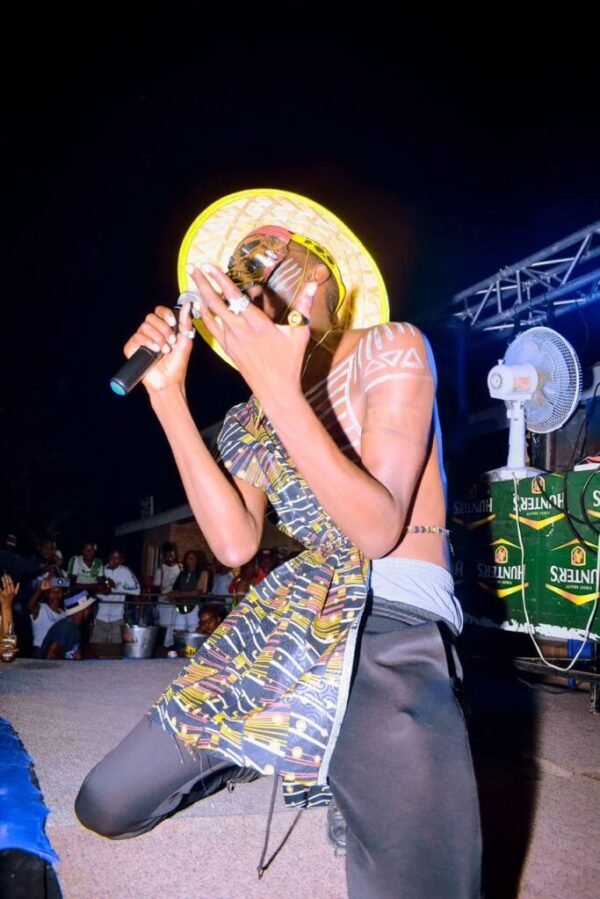

Now, for these young souls, speaking Wayei is like trying to catch the wind in a net. Yet, when Retiyo steps onto the stage and unleash the power of his ancestral tongue, people lean in, captivated, hanging on every word. It’s as if the spirit of the Delta itself flows through his voice, drawing them into the rich tapestry of their stories.

“Our traditions, like ancient baobabs, stand firm against the winds of change. Bongwale, a sacred passage where a girl, blossoming into womanhood, is cherished and celebrated after five days of quiet introspection, is but one shining example.”

He says their tables groan under the weight of delicacies like Tswii, Nxhuma, and Thapi, born from the fertile land and bountiful waters. They are keepers of the earth, their hands tending to pastoral farms and vibrant horticulture.

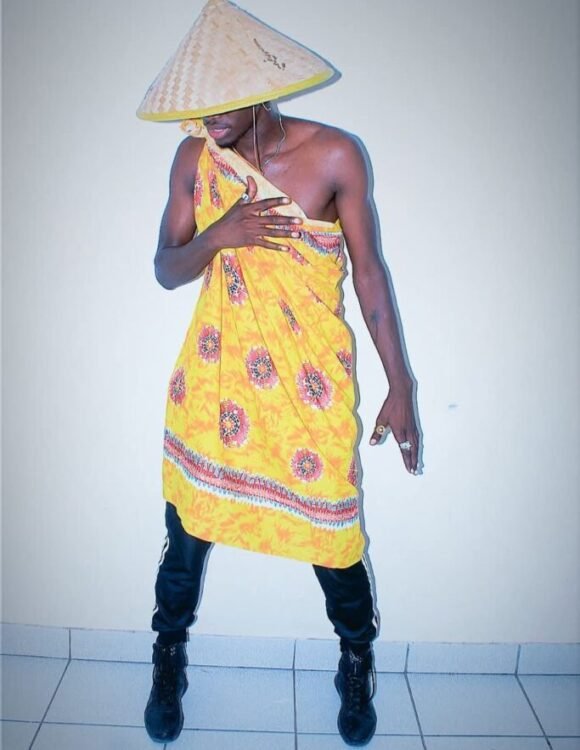

And when the sun dips below the horizon, the air thrums with the energy of Kharakhara and Seperu dances, their bodies adorned in the graceful Makgabi and Mojamburu. Yet, a shadow looms large, a specter of concern for their beloved Wayei tribe.

The younger generation, many of them speaking their language hesitantly or not at all, puts them at a crossroads. “We must stand tall, a united front, to ensure our culture doesn’t become a forgotten melody in the symphony of time.”

Retiyo’s music is a living testament to this fight, a vibrant echo of the Wayei heritage. The deep thrum of drums, resonant with the spirit of his Wayei ancestors, weaves through his songs, a heartbeat for their vanishing traditions.

“Singing in my native tongue is not just an artistic choice; it is an act of defiance, a sacred promise to keep our culture alive. To the young Wayei hearts who feel adrift, disconnected from their roots, I implore you: let us journey back, back to the wellspring of our being. Our culture is our pride, the very marrow of our bones.”

A nation without its culture is like a ship without a rudder, lost at sea. “Let us call upon our ancestors, their wisdom a guiding star, to lead us home. My dream, a beacon in the night, is to see the essence of my culture emblazoned in every magazine, every publication I lay my eyes upon. For I am a pure Wayei, and my heart beats for the preservation of all that we are.”